Given these massive changes, it is fair to ask why Beijing appears to remain committed to its quasi-alliance with Russia. What benefits does China receive and are they worth the risk to its relations with the West? Or is China merely shackling itself to a nation that increasingly resembles a corpse?

Before February, the grounds for this alliance were clear. Following the January 6, 2021 insurrection at the Capitol building, the United States appeared to be a nation in disarray, suffering hundreds of thousands of Covid-19 deaths, a chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan, and with millions of Americans adamantly denying the legitimacy of President Joe Biden’s administration.

Donald Trump’s policies had badly strained American relations with its European and Asian partners, many of whom still fear the right-wing nationalism he unleashed.

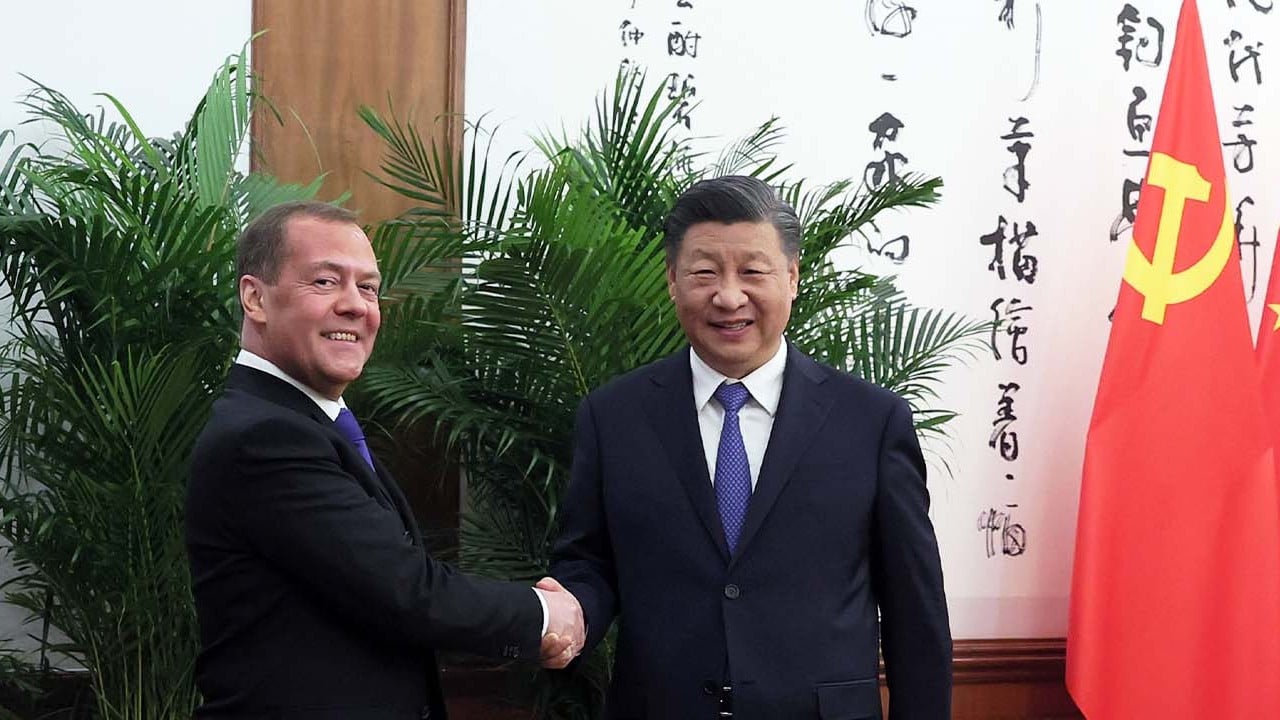

Chinese President Xi Jinping (right) and Russian President Vladimir Putin in Beijing on February 4. Photo: Kremlin via AP

China, on the other hand, was clearly a rising economic superpower with justified claims to have weathered the pandemic better than the US. And Russia was determined to demonstrate that it had arrested its post-Soviet decline, rebuilding its military machine into what many considered a first-rate professional force. Together, they posed a worldwide challenge to the United States.

Putin planned for his assault on an increasingly westernising Ukraine to achieve two goals: crush Ukrainian independence; and demonstrate to the US that Russia was its global equal. Leading up to the war, American intelligence reported on Russian plans to liquidate Ukraine’s political, economic, and cultural elites and to destroy an independent Ukrainian identity.

The Russian leadership envisioned the “special operation” lasting only a few weeks, after which it would oversee the establishment of new pro-Russian government in Kyiv. The victory would be both rapid and decisive, leaving Nato no other choice but to accede to Moscow’s conquest. This would be the first crucial step in the creation of a post-Western world.

Not only did the initial Russian attack fail spectacularly, Moscow’s military was both outfought and outthought by the smaller and less well armed Ukrainians. In addition, Ukraine’s heroic resistance united the West, convincing many nations across Europe to cooperate more fully with the United States.

Russia’s attempt to use its energy supplies as a cudgel to intimidate Europe from aiding Ukraine has also led to greater efforts by Europe to wean itself off Russian resources.

It is difficult to imagine that Xi Jinping could have anticipated such a turn of events when he stood with Putin in Beijing. Not only does China now face a West united in its outrage, but China itself is reeling from economic dislocations caused by overinvestment in its real estate markets and its shift away from zero-Covid that threatens significant outbreaks.

Furthermore, the Biden administration has launched a series of measures designed to limit technology transfer to China, that analysts say have decapitated China’s tech industry.

As the new year approaches, China’s leaders need to rethink their alliance with a diminished, reviled Russia as well as their efforts to exploit divisions within the West. Russia will never be the partner for which Xi had originally hoped: a counterweight to American conventional and nuclear capabilities.

Instead, many of Russia’s best military units have been destroyed by the Ukrainian military. Putin’s constant threats of nuclear war have even forced China to publicly state its opposition to the use of nuclear weapons in the conflict. Such statements demonstrate that Putin has become an unreliable partner.

Nor should Xi put much hope into separating America from its alliance partners. That is a century-old strategy, first used by Imperial Germany during World War I to weaken the tacit support of the US for Great Britain, then, later by the Soviet Union to pry the Western Europeans from America’s embrace. Both efforts failed.

Xi may be able to play to the vanities of European leaders who aim to demonstrate their independence from Washington; however, Putin’s weaponisation of Russia’s energy exports has made many Europeans resistant to forming ties that may come back to haunt them.

Scholars warn that the burgeoning Sino-American rivalry means the world has entered a dangerous new age of great-power politics with the possibility of global war at heights not seen in decades. Yet, even during the most dire periods of the Cold War, both the US and the Soviet Union sought to limit their potentially destructive rivalry.

So, too, it must be with the US and China today, especially given the upheaval the world has already suffered from the Covid-19 pandemic and Russia’s war with Ukraine.

Gregory Mitrovich was co-principal investigator for the project “Culture in Power Transitions: Sino-American Confrontation in the 21st Century”, funded by the United States Department of Defence, Minerva Research Initiative