So, women who have not paid into the system for the required number of years, or who do not have local basic medical insurance, still cannot enjoy maternity insurance. This means that rural migrant workers and those in unstable employment lack maternity welfare.

Secondly, there is the inequality of income distribution. China’s pattern of regional economic development has led to the formation of two extremes. In first-tier cities and other highly developed areas, the cost of living has become too high. But in the parts of the country where living costs are low, the basic wages, working environment and social resources are also poor.

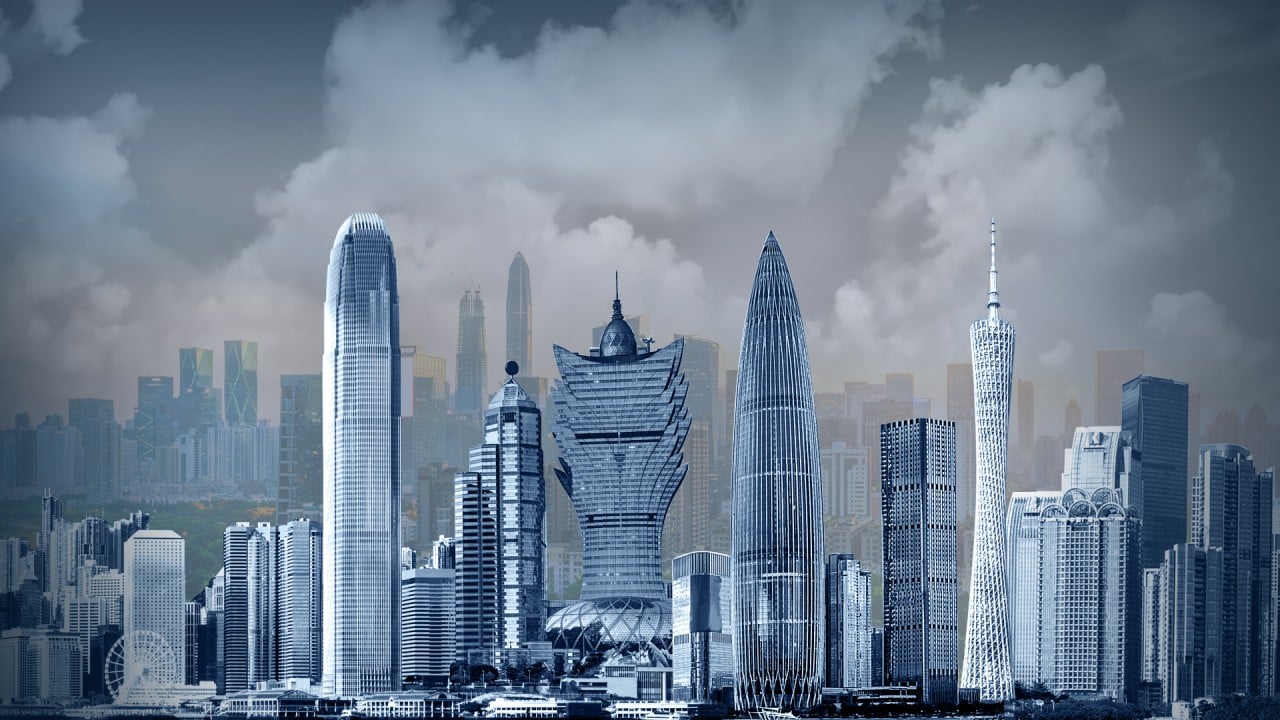

Pedestrians in Pudong’s Lujiazui financial district in the first-tier city of Shanghai, one of the most desired destinations for expatriates, overseas returnees and university graduates, on January 3. Photo: Bloomberg

China’s Gini coefficient – a measure of income inequality with 0.4 set as a warning level by the United Nations – has been growing, from 0.462 in 2015 to 0.466 in 2021. In particular, three years of Covid-19 and harsh pandemic restrictions have exacerbated the urban-rural divide and worsened income inequality.

For rural-urban migrants, the dilemma lies in the trade-offs. The urban job market offers higher incomes but also higher child-rearing costs and often, insufficient maternity welfare. Returning to rural homes to raise children would mean earning less. Leaving their offspring to earn in the cities turns them into left-behind children. For these migrants, the decisions around raising a family are extremely challenging.

Thirdly, with regional development so uneven, resources are more concentrated than ever in specific cities. This attracts intense competition and social pressures, so that many young people struggling to get a foothold start to question the necessity of marriage and children.

In 2021, the proportion of talent migrating to new and emerging first-tier cities rose to 35 per cent from 31 per cent, and a ranking of cities’ business attractiveness found that the 10 busiest with residential activity were: Hangzhou, Chengdu, Chongqing, Dongguan, Suzhou, Wuhan, Nanjing, Zhengzhou, Foshan and Xi’an. These cities are all clustered in the east, south and southwest of China.

This generation of “talent” is acutely aware that the stresses of their personal lives might be exacerbated by having children. Despite China’s vast lands, the field of competition and the opportunities to improve the quality of life are concentrated in a narrow band, making it hard to make moderate migration choices.

For the well-educated, choosing developed regions with talent attraction policies makes it easier to achieve career advancement and find more diverse opportunities. For rural-urban migrants, the need to find better-paying jobs drives them to the same choice.

But this only leads to an increasingly skewed allocation of social resources. For example, China has nationwide talent attraction policies with benefits that vary little, if at all, among the regions, yet most continue to be attracted by the megacity clusters, such as the Greater Bay Area, Yangtze River Delta, Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei, and Chengdu-Chongqing, because of the superior infrastructure and working environment.

Shanghai, in particular, which had a skilled workforce of 6.75 million people last year, is the “top choice for expatriates, overseas returnees and college graduates looking to further their careers”, according to Yicai Global.

In the long term, China needs its regional development to be more even so it can build public trust and a greater sense of security.

Even when it comes to something as basic as medical care, many Chinese people I know still seek out first-tier hospitals because they believe they are getting the best; this includes those who already live in second- and third-tier cities, never mind those from the rural areas.

They would rather queue for an appointment months in advance just to be able to see a doctor in a big city hospital – bearing the higher costs of the journey because they believe they will receive a better public service.

In my opinion, China’s urbanisation strategy does not take enough account of the impact of such high-speed urbanisation on people’s perceptions of life.

If the quality of public and social services is raised to a similar level throughout China under a high-quality urbanisation strategy, public trust in regional development will improve, halting the stampede for the few elite cities and decentralising social pressures. And it might just improve people’s attitudes towards having children.

Jinyuan Li is a research candidate in global affairs at King’s College London