The situation has led to the emergence of content moderation with Chinese characteristics, with numerous data companies available to screen material before it reaches the public sphere.

People’s Daily – mouthpiece of the ruling Communist Party and arguably best placed to identify Beijing’s shifting and often vague red lines – is also offering to sell its expertise to companies wishing to eliminate potential political risks.

Its product Renmin Shenjiao was launched in July last year, just months before the 20th party congress.

China’s growing market for outsourced content censorship and the heavy focus on political sensitivities come amid the party’s push in recent years for ideological dominance and conformity, according to observers.

Like other countries, violence, pornography and hate speech are unacceptable on Chinese social media. But, while the power to control content is more diverse in the West, in China it is concentrated in the hands of the ruling party.

The increasing reliance on external pre-screening by Chinese government agencies, state-owned enterprises and private companies offers a glimpse into their struggle to avoid political red lines that are not always explicit until they are crossed.

Despite the different approaches to content moderation, observers said all countries had one thing in common – the growing volume and complexity of material meant artificial intelligence would inevitably replace human eyes.

According to some estimates, the amount of data generated each day by social media globally could reach 463 billion gigabytes by 2025.

Already, the social media management platform Hootsuite puts Twitter’s daily active users at 238 million, with at least 500 million tweets per day.

In 2013, state-owned Beijing News reported that an estimated two million people in China were employed to manually monitor and analyse online content.

In the United States, Facebook had about 15,000 content moderators in 2020, while Chinese tech firm ByteDance reportedly employs more than 20,000 in that role.

Artificial Intelligence is already used in China and other countries to help with the task, though Renmin Shenjiao – which means People’s Proofreading – assures potential customers that it also uses human censors.

Advertisements for the product which appeared in People’s Daily in June said Renmin Shenjiao’s services include screening of written materials, photos, videos, and posts on social media platforms, including WeChat and Weibo.

A sales handout for potential clients seen by the South China Morning Post lists an annual fee of between 46,000 yuan and 99,000 yuan (US$6,400-$13,700), depending on how much material needs to be screened.

Clients upload material to the platform for review by AI and a team of censors. Content that could be flagged as risky includes material related to ideology, religion, purged government officials, Chinese dissidents, and maps related to disputed border areas.

According to the sales document, animations of government leaders, content related to their relatives, and references to disgraced celebrities would also be picked up as potential risks.

A Renmin Shenjiao sales representative said clients included public institutions and state-owned enterprises, as well as a smaller number of private companies.

It is not rare for businesses in China to find themselves under fire when their content is deemed to overstep a political red line.

Last year, the show of China’s most popular e-commerce influencer Li Jiaqi came to an abrupt end on June 3.

While he later said the suspension was due to a “technical error” there was speculation that authorities forced Li to end the show after he displayed an ice cream shaped like a tank – an image associated with the Tiananmen Square crackdown on June 4, 1989.

A Beijing-based entrepreneur in the chat AI industry said any content or communication-related business in China had to go through content moderation to survive.

“Any ads that you see have been checked or otherwise they will just not survive. The market has always been there, and AI has been used in content moderation software for a long time,” said the entrepreneur, who asked not to be identified.

Stepping on Beijing’s political red lines, even unintentionally, could prove very costly to any company and could add to the already difficult and competitive business environment, the entrepreneur said.

Most content moderation software is provided by China’s major tech companies, which feed in regular updates on new rules or sensitive topics and events, according to the entrepreneur.

Tech companies Alibaba, which owns the South China Morning Post, and Tencent provide content moderation under their cloud services units.

Tencent Cloud’s AI algorithm models can be applied to platforms, including live-streaming sites, to identify videos, photos, audio and texts. Alibaba’s counterpart service covers photos and texts, and identifies spam as well as political and other sensitive content.

While Renmin Shenjiao’s algorithm generally might not be as strong as its tech company rivals, the idea is that it will be better at filtering political content, according to a person with knowledge of the product.

This was because Renmin Shenjiao staff were part of the People’s Daily group, and may have knowledge of new taboos that were otherwise not known to the public, the person said.

Analysts caution that the rising demand for political content screening services is a worrying sign of China’s tightening information environment. The boundary is also evolving, with more ambiguity regarding new taboos, they say.

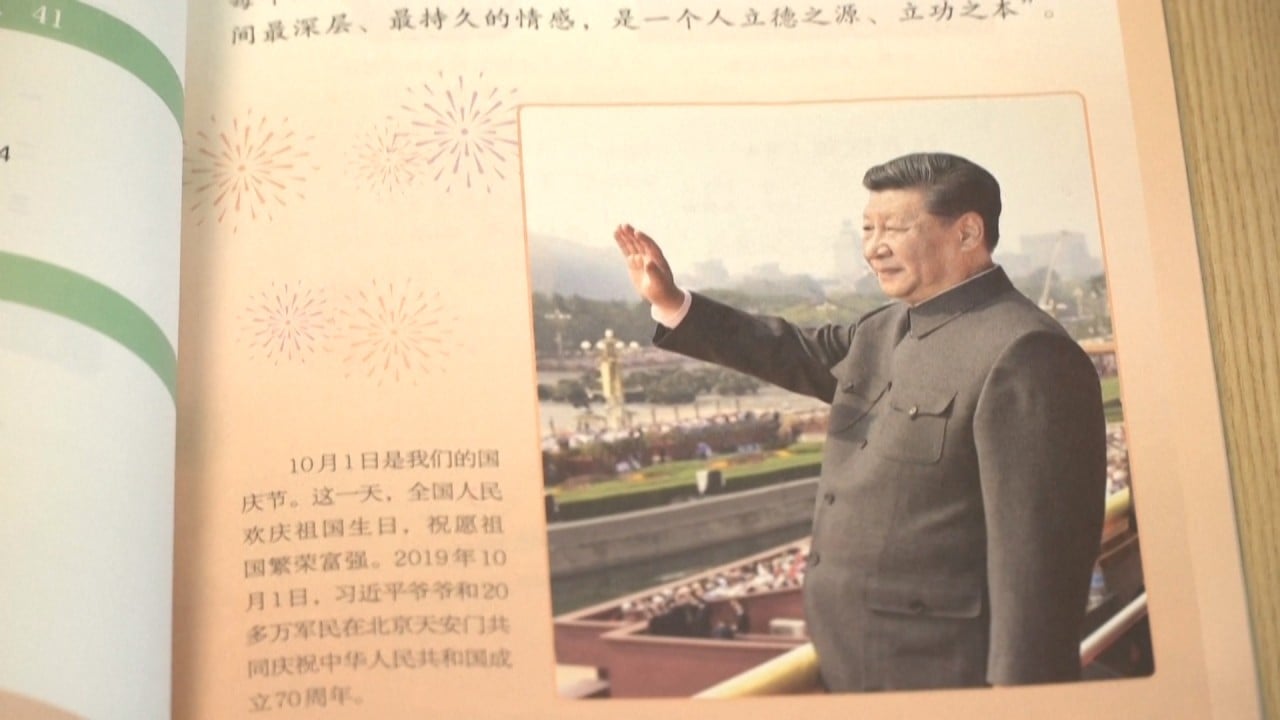

The fact that the services were so openly marketed suggested “the internal politics of party operations are becoming increasingly controlled as the Xi Jinping era progresses”, said Neil Thomas, a fellow in Chinese politics at the Asia Society Policy Institute’s Centre for China Analysis.

In Thomas’ view, the aim is to ensure “greater ideological conformity within the party state”. He noted that content moderation in China had a focus on political sensitivity, while Xi “places great value on political correctness”.

Thomas said the increasing demand for absolute ideological uniformity was also affecting private firms, as scrutiny and the risk of something going wrong extended beyond government agencies.

“Everyone is expected to toe the party line in their public statements and the political risk for private firms of being even accidentally unaligned with Xi Jinping Thought is steadily increasing,” he said, referring to Xi’s political doctrine that was enshrined in the country’s constitution in 2018.

“Companies that want to maximise profit will rationally acquire content moderation services that minimise the risk of overstepping political boundaries or being out of sync with Xi Jinping Thought.

“I think this shows that China is the global centre of censorship and China is at the forefront of innovation when it comes to new ways to strengthen the censorship process.”

According to Thomas, the repercussions of political comment on social media in the West come mostly from citizens with different ideologies, resulting in a populist backlash rather than official or legal sanctions.

“Political risks are issues that companies face everywhere. It’s just that in China, the level, the intensity and the explicit legal consequences of straying from political correctness are much greater than in the West,” he said.

Rana Mitter, a professor of the history and politics of modern China with the University of Oxford, said many countries automated the process of moderating social media as much as possible “and put the responsibility in the hands of the user, not the state”.

“The difference is that in China, the motivation and the impetus is coming from the party itself, top-down. In the liberal world, it’s coming from companies like Meta, Alphabet and so forth,” he said.

Mitter said one of the primary goal’s of Beijing’s content moderation regime “is to make sure that the ideological dominance of the CCP – which is now very strong in China – continues to operate”.

He noted that the demand for content moderation also came amid concerns about controlling nationalist ideas in China, with some netizens appearing to be more nationalist than the government, which right now might “look to be a bit more subtle, more nuanced” in its relations with other countries like the US.

Mitter said China’s information environment had tightened over the past decade, and that “there is a very strong top-down demand from the party in the government that the language, particularly around politics but also [the more broadly defined] cultural issues must be very heavily censored”.

Mitter predicted that outsourced content moderation services would become more widely used, even by individuals, when ambiguity arose. “[What] the party state considers sensitive is sensitive,” he said.

“Right now, the definition of what is ‘security sensitive’ in China is being expanded very significantly. But also the lines are not being drawn clearly. The problem is that’s going to be very chilling to atmospheres of entrepreneurship and innovation,” Mitter said.