Across the foreign policy communities of the US, however, the narrative seems straightforward: the root of the problem lies in China.

Yet since May 1, 2019, China has included all fentanyl-related substances in its controlled list of narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances with non-medical use. This makes China’s drug scheduling policy, which includes the prohibition of exports, one of the strictest in the world. In contrast, fentanyl scheduling in the United States, while recognised as an effective measure, is a matter of federal and state prerogative.

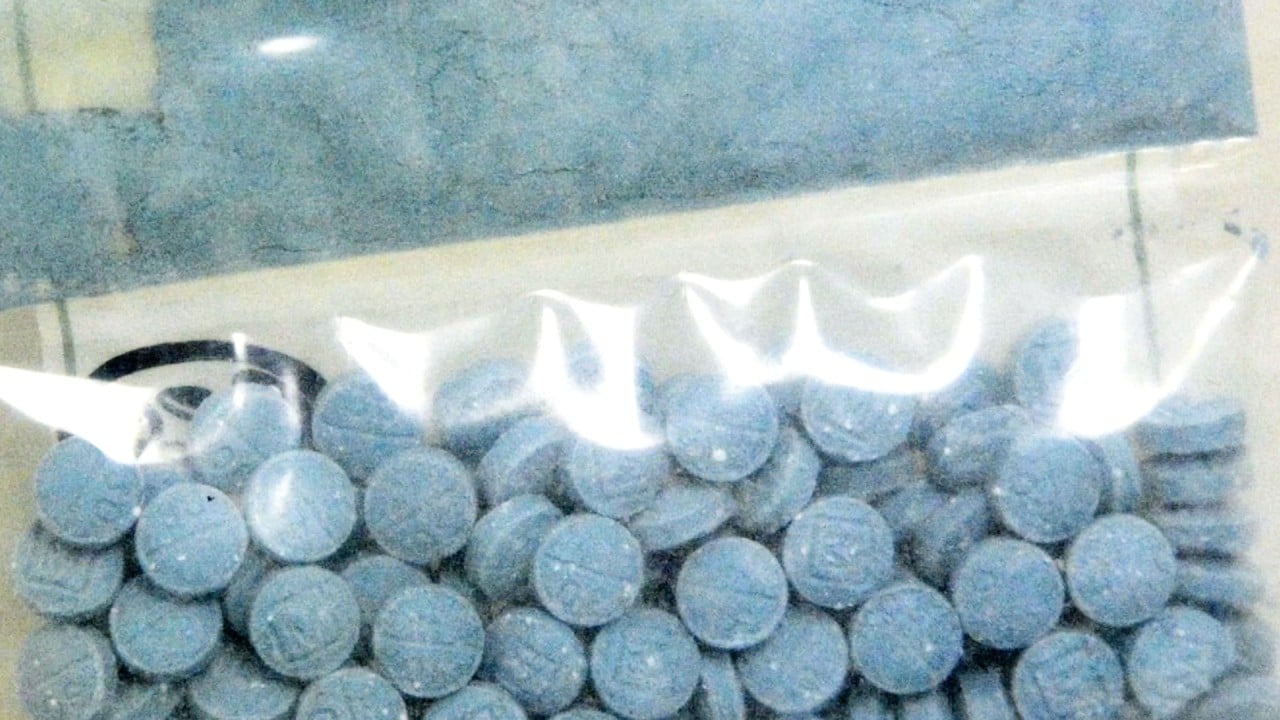

But even those who credit China’s efforts note the emergence of new fentanyl precursor chemicals that elude its ban, allowing drug cartels in Mexico to make and smuggle fentanyl – often laced with heroin – into America.

China maintains it has worked with the US to help deal with its fentanyl abuse crisis and sees it as a firmly American problem.

Given this, if there is to be a positive outcome from the US-China fentanyl discussions expected on the sidelines of the Apec summit in San Francisco, there has first to be a de-escalation in the diplomatic finger-pointing on both sides.

Cross-border flows of illicit drugs have a long history, as do the political complexities behind the attribution of cause and effect. Still, there are very strong reasons to untie the knot of US-China acrimony over fentanyl.

First, there has to be a broader acceptance of the unique challenge that illicit fentanyl poses. Unlike, say, heroin or cocaine, which are plant-based, fentanyl is a synthetic drug. In any society, its manufacture, trafficking and abuse would be a malaise hard to eliminate. Law enforcement and public health authorities, as hard as they try, are invariably crisis-driven and stuck in a responsive mode.

This recognition demands that both American and Chinese foreign policy observers go beyond the usual conceptual mode of placing “geopolitical trust”, a vague notion to begin with, at the root of the level of cooperation or lack of – whether real or perceived.

Second, illicit drug markets are incredibly resilient. When one society steps up control, as the US is doing, it is contributing to the prevention of a faster and more global spread. The world community stands to benefit from that government’s efforts, including through international cooperation.

In other words, any cooperation of the Chinese authorities in stemming newly identified chemicals that are proven to have gone to the workshops of illicit drug manufacturers would be not so much in a “humanitarian spirit” as a pre-emption of the same ill fate falling on their own society.

Blaming China for fentanyl threat won’t solve America’s opioid crisis

Blaming China for fentanyl threat won’t solve America’s opioid crisis

Third, if China and the US can let go of the bad sentiments – that China is condoning a “reverse opium war” or the US is simply outsourcing its domestic problem – their law enforcement and public health authorities would gain much-needed political and policy space to conduct evidence-based exchanges and cooperation.

The educational, scientific research and healthcare entities and individuals of both countries should be able to work without worrying about political issues like “national security” or “state intent”.

The most desirable scenario of a Xi-Biden meeting at the Apec summit in San Francisco would be the public announcement of a US-China decision to return to full public health cooperation. Simply put, it would be responsible politics and policymaking to allow scientists, and public health and law enforcement officials in both countries to resume the interactions they require to do their jobs properly.

Settling for anything less than full cooperation would be a lost opportunity to stop the flow of chemicals known to be the culprits of illicit products in circulation in the United States.

Zha Daojiong is a professor of international political economy in the School of International Studies, Institute of South-South Cooperation and Development, Peking University