China’s nominal gross domestic product (GDP) could grow by about 1 percentage point as a result of the bond issuance, he added.

“Local officials probably won’t face quite the same pressure to deliver now, as the central government is taking on a greater role, but it doesn’t exactly augur well for potential growth in the medium and long term,” Beddor said.

Investment banks and other institutions have forecast lower Chinese economic growth after 2024 as the bond issue would not solve underlying problems, analysts said.

“One trillion yuan, while no drop in the ocean, is just a one-off for now,” said Heron Lim, an assistant director and economist at Moody’s Analytics.

“It is a rare occurrence for China to adjust its budget midterm, so it is more of a fiscal stimulus. Tapering is to be expected.”

China’s economy would grow by 4.9 per cent in 2024 and 2025, according to Moody’s Analytics, but will then fall to just 4.3 per cent expansion in 2026.

Fitch Ratings, meanwhile, forecasts growth of 4.8 per cent next year and 4.7 per cent in 2025.

DBS Bank predicts 4.5 per cent growth in both 2024 and 2025, while HSBC’s outlook puts growth at 4.6 per cent next year followed by 4.4 per cent in 2025.

Average annual growth should reach 4.9 per cent from 2021 to 2025 and 3.6 per cent from 2026 to 2030, said Alicia Garcia-Herrero, chief Asia-Pacific economist with French investment bank Natixis, in a report in June.

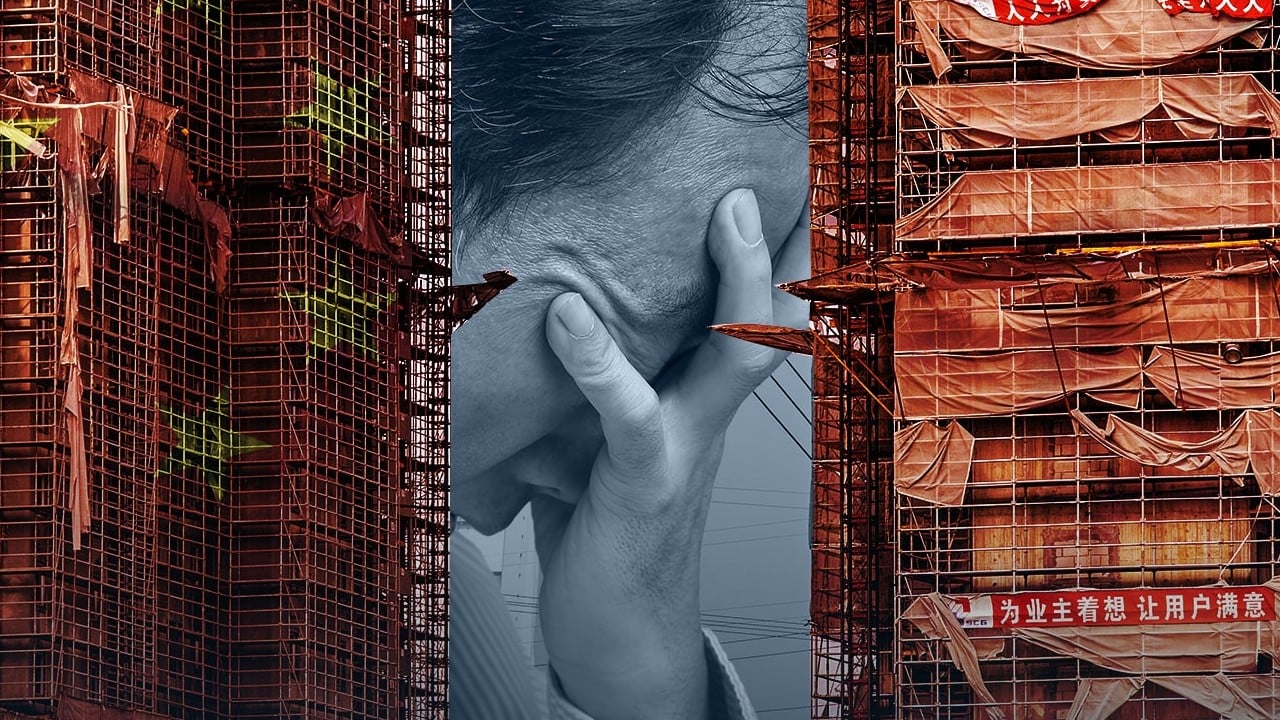

Among the lingering issues, China’s property sector is “projected to remain subdued”, DBS senior economist Nathan Chow said.

The government has tried since 2020 to reduce systemic risks from overleveraged developers by removing weaker ones from the loan and bond markets.

But some of China’s largest developers, including Country Garden and Evergrande, have gone into default.

Goldman Sachs anticipates that the property sector would make a net negative GDP contribution until the end of 2030.

Government debt is also likely to “rise further” even though local finances are under pressure amid “weak” land sale proceeds and a push for more spending, Fitch Ratings said in July.

Shaky financial health has challenged local governments to pay back their debts without wider economic growth, creating a worry for policymakers and investors.

China’s GDP forecasts raised by IMF, but property sector woes may hinder growth

China’s GDP forecasts raised by IMF, but property sector woes may hinder growth

The coronavirus pandemic “may have left significant scarring effects, such as structurally high youth unemployment”, Garcia-Herrero added.

China’s export-led, investment-fed economy grew by close to 10 per cent, often higher, every year from 2002 to 2011, but the impacts of coronavirus containment measures hurt the growth rate from 2020 until last year.

Officials in Beijing cite weak economies in other countries – the buyers of Chinese exports – and other external problems as barriers to GDP growth.

The central government would approve new policies and funding to resolve its economic issues, analysts said.

As China’s debt risks mount, the spectre of looming local crises rears its head

As China’s debt risks mount, the spectre of looming local crises rears its head

Government-led investment in public housing and “urban village” renewals should “buffer the decline in property investment,” Goldman Sachs said on Sunday.

Officials may increase spending to support the economy and raise youth employment, despite the risk of generating debt, said Chong Ja Ian, an associate professor of political science at the National University of Singapore.

Hidden debt refers to informal financing by local government vehicles for projects such as roads and housing.

Planners would also try to raise employment among college graduates, Zheng added.