Wang Yiming, central bank adviser and former vice-president of the Development Research Centre of the State Council, said that China’s growth model, based on debt-fuelled investment and land sales, has become difficult to sustain.

We cannot rule out the resumption of monetary tools

“Debt accumulated in the past has led to huge repayment and risk exposure, and as such it has inhibited the demand for investment [that it has been funding],” Wang said at the 2024 China Bond Market Forum in Beijing on Friday.

Besides fiscal expansion, Zhang Ming, deputy director of the Institute of Finance and Banking at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, said the country’s central bank will also be ramping up support.

On January 2, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) loaned 350 billion yuan (US$49.2 billion) to policy banks through its pledged supplementary lending (PSL) facility in December.

The PBOC, however, did not say how China Development Bank, Export-Import Bank of China and Agricultural Development Bank of China would use the loans.

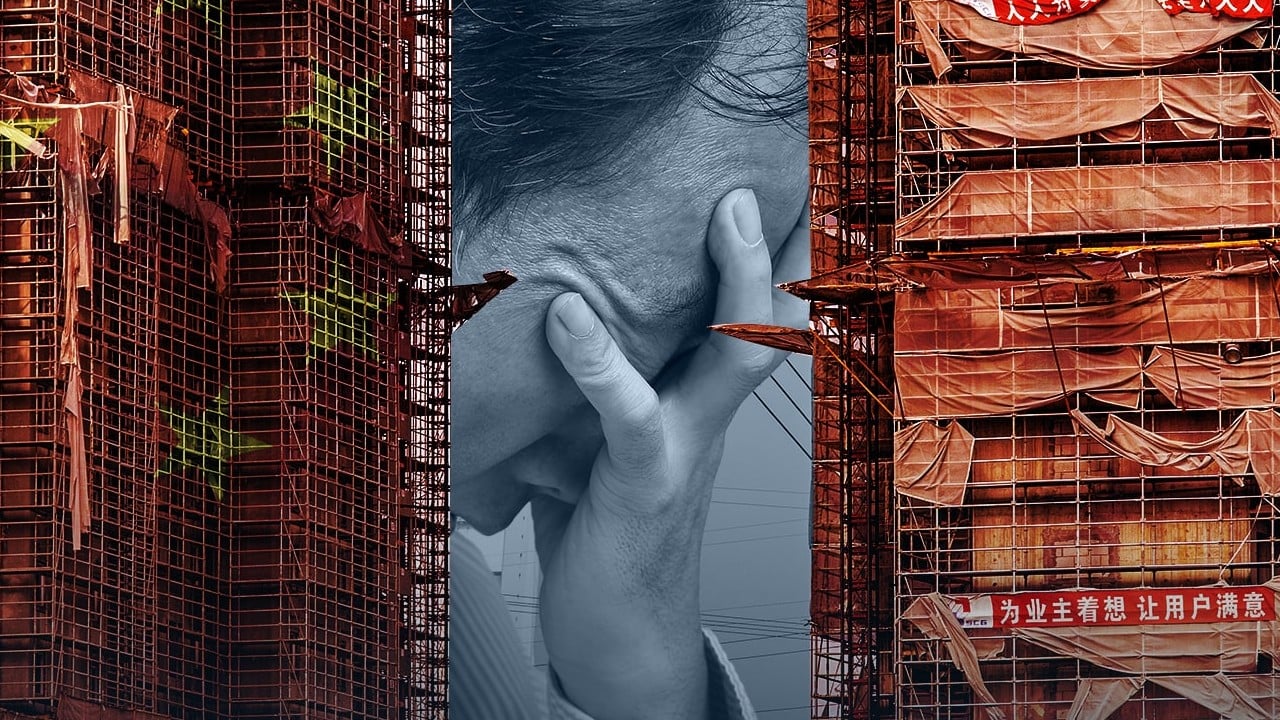

Stagnant market has some Chinese developers shirking payments to contractors

Stagnant market has some Chinese developers shirking payments to contractors

“The PSL [loan size] in December was the third-highest in history,” said Zhang, also a speaker at the bond market forum. “I believe the funds may go into the big three constructions in 2024. We cannot rule out the resumption of monetary tools [such as PSL].”

The PSL programme, initiated in 2014, is designed to help the central bank better target medium-term lending rates while boosting liquidity to specific sectors by offering low-cost loans to selected banks. China relied heavily on PSL loans to support its shantytown renovation programme from 2015 to 2018.

On average, LGFVs pay yearly interest of 6 to 8 per cent, while the new refinancing bonds offer just 3 per cent or below.

Wang Tao, chief China economist at UBS Investment Bank Research, said she expects the central government, which has a much lower level of debt, to provide more explicit aid. This could mean China’s budget deficit target will be set at 3.5-3.8 per cent of gross domestic product, Wang said.

In addition to the 1 trillion yuan in special treasury bonds from 2023, China may sell another trillion in 2024, Wang estimated, adding local governments may be allocated a total of 4 trillion yuan in special purpose bonds for infrastructure investment.

“We also expect continued restructuring for local government debt – including extending loan duration and lowering interest rates, as well as issuing another 2 to 3 trillion yuan in bond swaps to help ease LGFV payment issues,” Wang said.