Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Climate change myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

India is braced for “severe heatwaves” during its general elections as public health experts warn that hundreds of millions of voters are at risk and local authorities fear turnout may be affected by record summer temperatures.

Nearly 1bn people, out of a population of 1.4bn, are expected to vote over the next six weeks in staggered rounds of polling that will end on June 1.

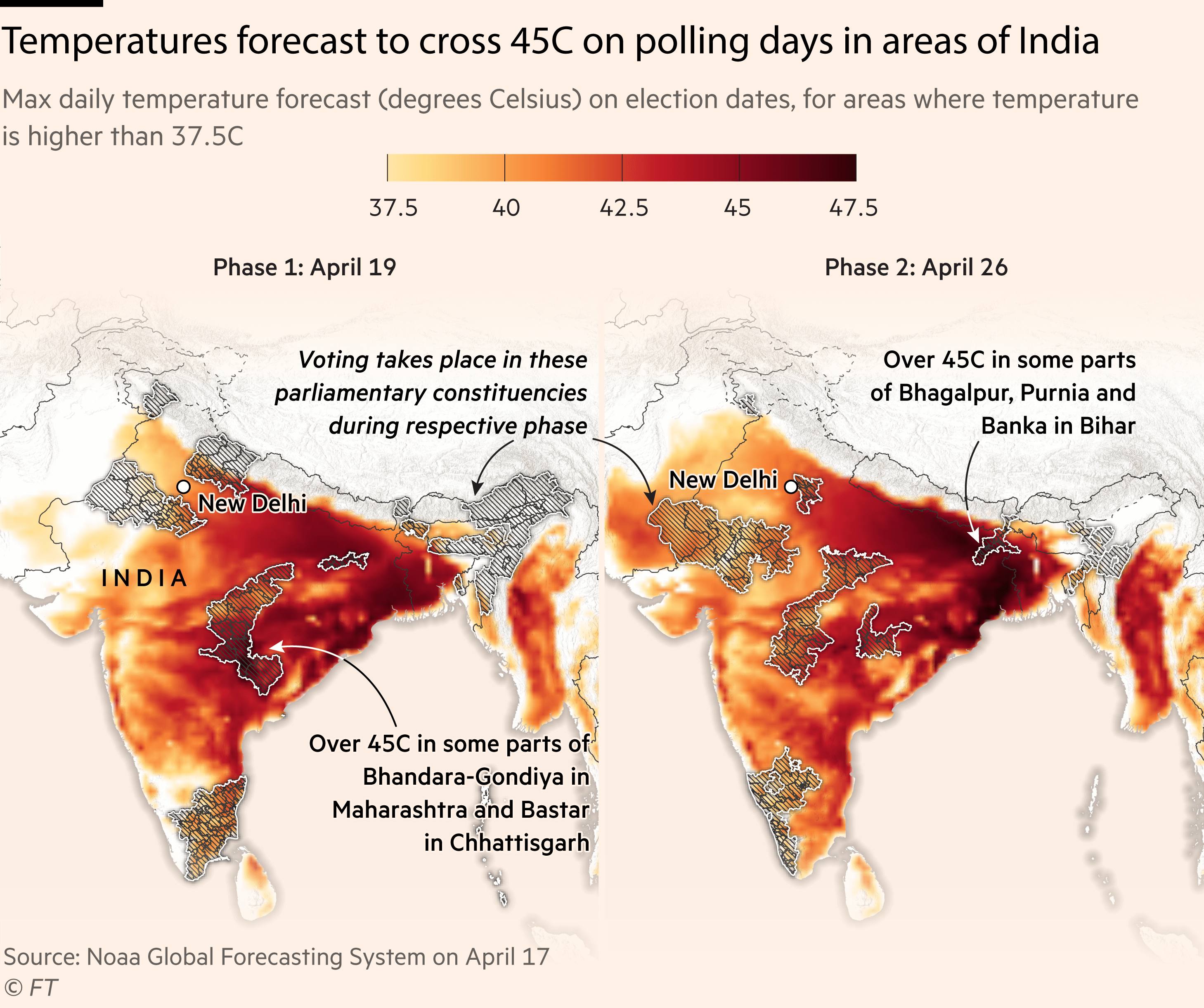

The extended period of outdoor rallies, roadshows and polling will coincide with temperatures expected to exceed 45C in places. On the first day of polling on Friday, temperatures were already at 42C in some constituencies in Maharashtra, the third most populous state.

The India Meteorological Department expects 10 to 20 days of heatwaves between April and June — more than double the typical summer average of four to eight days.

Authorities are making preparations for the extreme heat, with Prime Minister Narendra Modi last week chairing a meeting of India’s National Disaster Management Authority.

Kiren Rijiju, a government minister, recently told local media that voters would be gathering “while braving severe heatwave conditions”.

Around the world climate change caused by greenhouse gas emissions as a result of burning fossil fuels have been behind tumbling records over the past year.

Global average land temperatures in March exceeded the pre-industrial average for the month by 1.68C. Each fraction of a degree of warming exacerbates weather events.

The dangers from rising temperatures have already taken a high toll on India. An estimated 1,116 deaths were attributable to heatwaves annually across 10 major cities, according to the latest academic study.

Last April alone, 14 people died and hundreds suffered heatstroke after a rally of Modi’s Bharatiya Janata party in Maharashtra. This year, temperatures which are more than 7C above average for early April reportedly caused dozens of visitors to the Taj Mahal in north India to faint.

“One problem with climate change is that it has toppled all the predictions,” said Anjal Prakash, a climate researcher at the Indian School of Business. Prakash added that while elections had previously taken place during summer “we do not have much precedent for this”.

“The way in which we’re warming up so early, so fast — that has been a recent phenomenon,” Prakash said.

The confluence of heat and elections underscores how India, the world’s most populous country, is among the places most vulnerable to the increasingly intense and frequent weather events related to climate change, from dangerous heat to violent monsoon rains.

While the BJP and its rival Indian National Congress party have pledged in their manifestos to promote the energy transition, climate change has been largely absent from grassroots campaigns in heat-stricken areas.

“The manifesto is one thing but the actual [reality] on ground is another,” Prakash said. “There are other emotive issues on which elections are fought.”

The country has scaled up renewable energy capacity under Modi while it continues to rely heavily on coal for most of its power, and also sought to improve local preparedness for heatwaves and extreme weather.

Nikunja Dhal, the chief electoral officer for Odisha, an eastern state of more than 40mn people where temperatures were past 43C this week, said the authorities had told parties not to campaign outdoors between 11am and 3pm. Drinking water and paramedics would be made available on voting days, he said.

“It’s much more challenging this time compared to the previous elections,” Dhal said. “It could definitely affect turnout to some extent because it’ll be difficult for people to come out [during the day].”

Public health experts say that often state measures are only loosely enforced on the ground, however. Researchers have reported that early warning and preparedness systems have only recently been made a matter of policy at the city government level.

Avikal Somvanshi, an environmentalist at the Centre for Science and Environment think-tank, said it was “not sustainable” to hold elections during the summer and they should be conducted at other times of year. Some previous general elections have occurred in cooler months, such as in October and February.

“People are forced to line up outside these voting centres and these lines can take hours,” Somvanshi said. “We can’t go ahead doing elections in such harsh conditions without doing major infrastructure building.”

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here