Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what the 2024 US election means for Washington and the world

Resilience is a good thing. We’ve learnt that over the past two decades or so — pandemics, wars, trade decoupling and climate-related disasters have made the risks of over-concentrating production capacity in any one place apparent.

That’s why I’ve always believed it to be a good thing to have more regional nodes of critical goods manufacturing around the world. It’s not about ideology. It’s just about not keeping all your eggs in one basket.

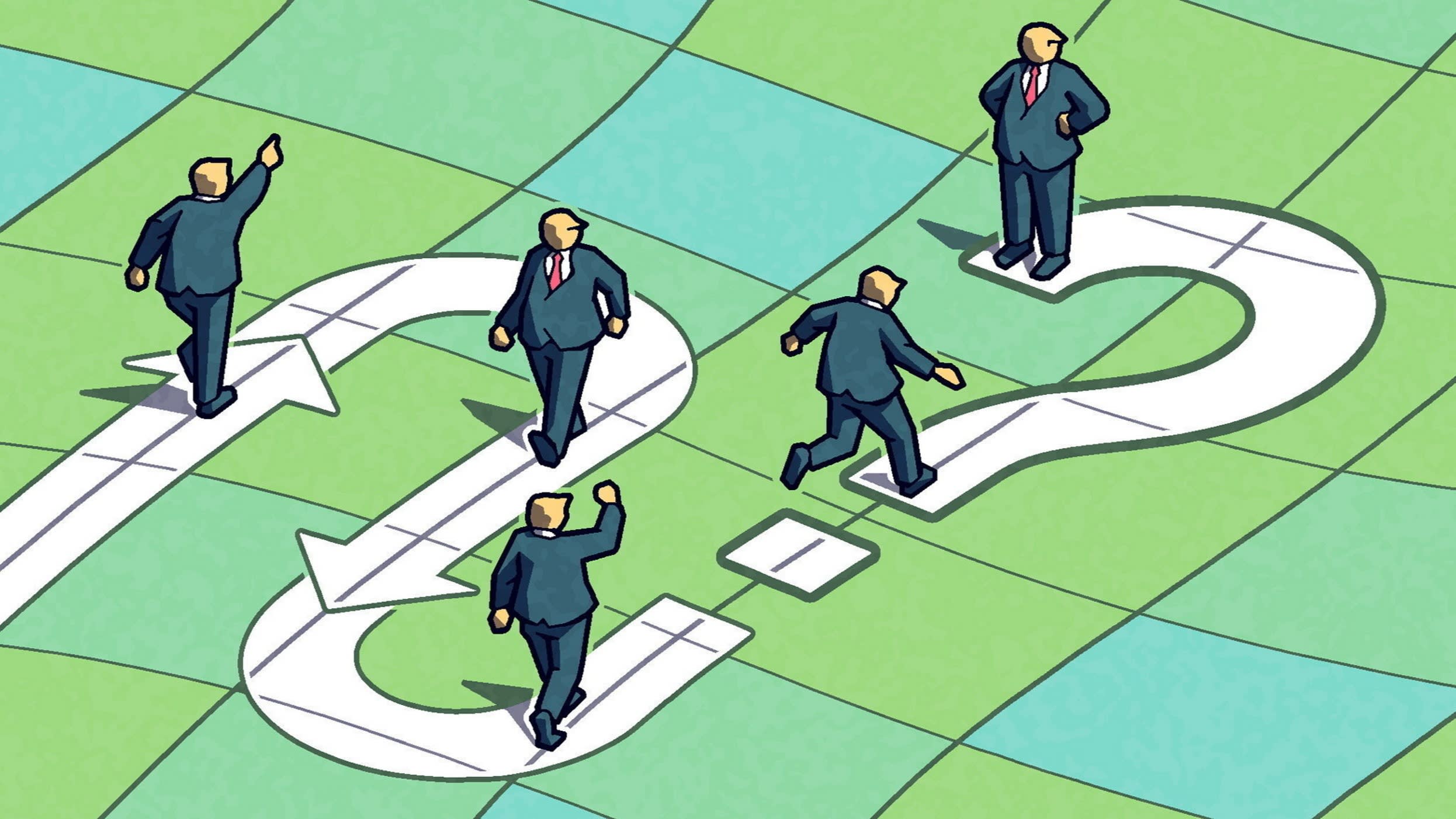

But to create resilience, you need to play both offence and defence. The Trump administration is trying to do the latter with tariffs in a way that is incoherent, at best. But even if its tariff strategy were surgical (right now, we have blanket tariffs on high- and low-value parts of the economy alike, and proposals that shift by the day), it would fail without a home game that includes industrial policy to bolster truly strategic industries. Only countries that have both, and connect them clearly, can successfully boost domestic manufacturing.

During the Biden administration, the US used a combination of trade, capital and technology restrictions, as well as domestic industrial policy in the form of tax breaks, grants, subsidies and worker training programmes, to bring back crucial industries like semiconductor production to America.

No one said this was going to magically replace all the factory jobs lost to China over the past 20 years or so, but there was a clear message that the US needed to be able to produce at least some of the components that were the lifeblood of the digital economy on its own soil. Quite wisely, the EU followed suit.

The fact that resilience in a complex critical industry like chips could be restored in a little over two years should have been a case study for the Trump administration to follow in key areas from critical minerals to pharmaceuticals. But what we’re getting is policy made in dribs and drabs, with some blanket tariff proposals, some industry-specific national security investigations in areas including copper, lumber, chips and pharmaceuticals, and proposals for domestic support of industries like shipping, but without actual subsidy support or workforce training commitments locked in yet.

None of this tells business — domestic or international — what the US cares about in terms of manufacturing, and why. That, in turn, creates uncertainly that isn’t conducive to the kind of investment that the White House says it wants to bring to the US.

As trade expert and former US China Economic and Security Review Commission member Michael Wessel puts it: “Major public firms look to investment metrics that are often five years or longer. No one knows how long tariffs may last either during this administration, or beyond.

“Without the industrial policies in place, markets may not have the confidence” to pour money back in to the US, particularly in areas like manufacturing or energy, which have even longer timelines for return on investment.

Even if the Trump administration was being clear about exactly where it wants to build capacity, it would need to go much deeper on tariff design to guard against things like “tariff inversion”, when duties on imported component parts end up being higher than on finished goods, hurting domestic manufacturers.

Likewise, it would need to tabulate supply chain risk in far more sophisticated ways. Donald Trump is telling the American public that he can get manufacturing back up and running within one and a half to two years. But where will the electricity and energy to run them come from, particularly if there are tariffs on suppliers such as Canada?

The grid system is outdated and under-resourced in many places across America, and power generation plants (of which the US is short) take years to build. Meanwhile, no amount of deregulation is going to make domestic shale energy viable if the price of oil keeps falling.

Then there are the inventory issues. US companies tend to keep very little inventory on hand because of just-in-time production models. That matters a great deal when there are sudden retaliatory limits on rare earth minerals from China, or export bans by places like Democratic Republic of Congo — one of the only other countries where the critical mineral cobalt can be sourced. As one risk analyst told me, these types of disruptions can collide to shut down production in areas such as electrical vehicles, medical devices and aerospace materials. I could name 12 other such downstream risks, but you get the idea.

Is anyone in the Trump White House developing a 360-degree view on all this? I don’t know for sure, but I’m guessing no.

I wish this administration would do what I advocated in a column several years ago: hire an ex-military or logistics expert to be a White House level resilience tsar. The physical and financial risk factors in play are head spinning, and someone needs to start thinking carefully about how they may collide.

Unfortunately, the White House seems focused on the same old conservative prescriptions. Council of Economic Advisers head Stephen Miran has played down the risk of tariffs and said tax cuts and deregulation would make America more globally competitive. That sounds less like a resilience plan and more like wishful thinking.