Medical device makers have raised the alarm over a potential supply chain crunch and higher prices for hospitals around the world because of the disruption from the US-China trade stand-off.

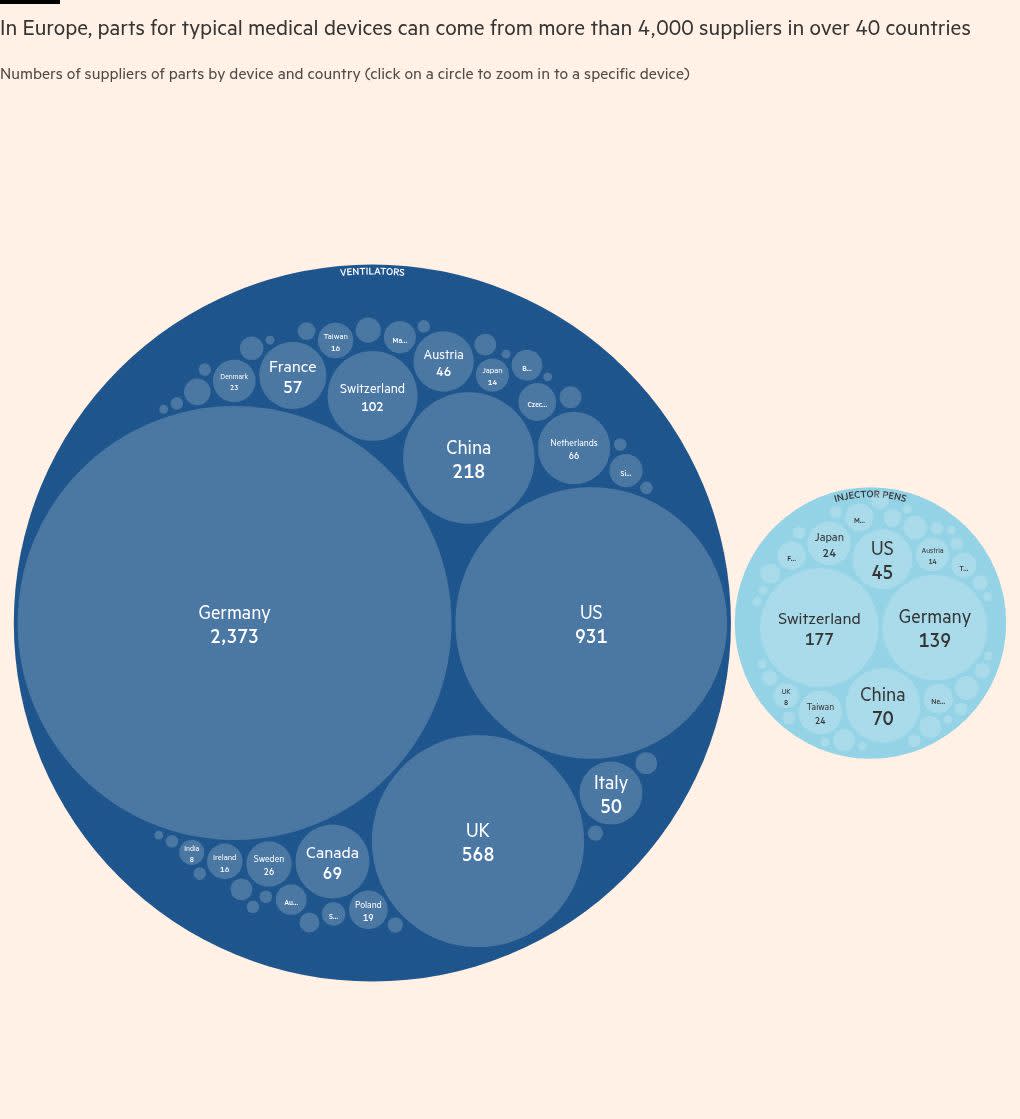

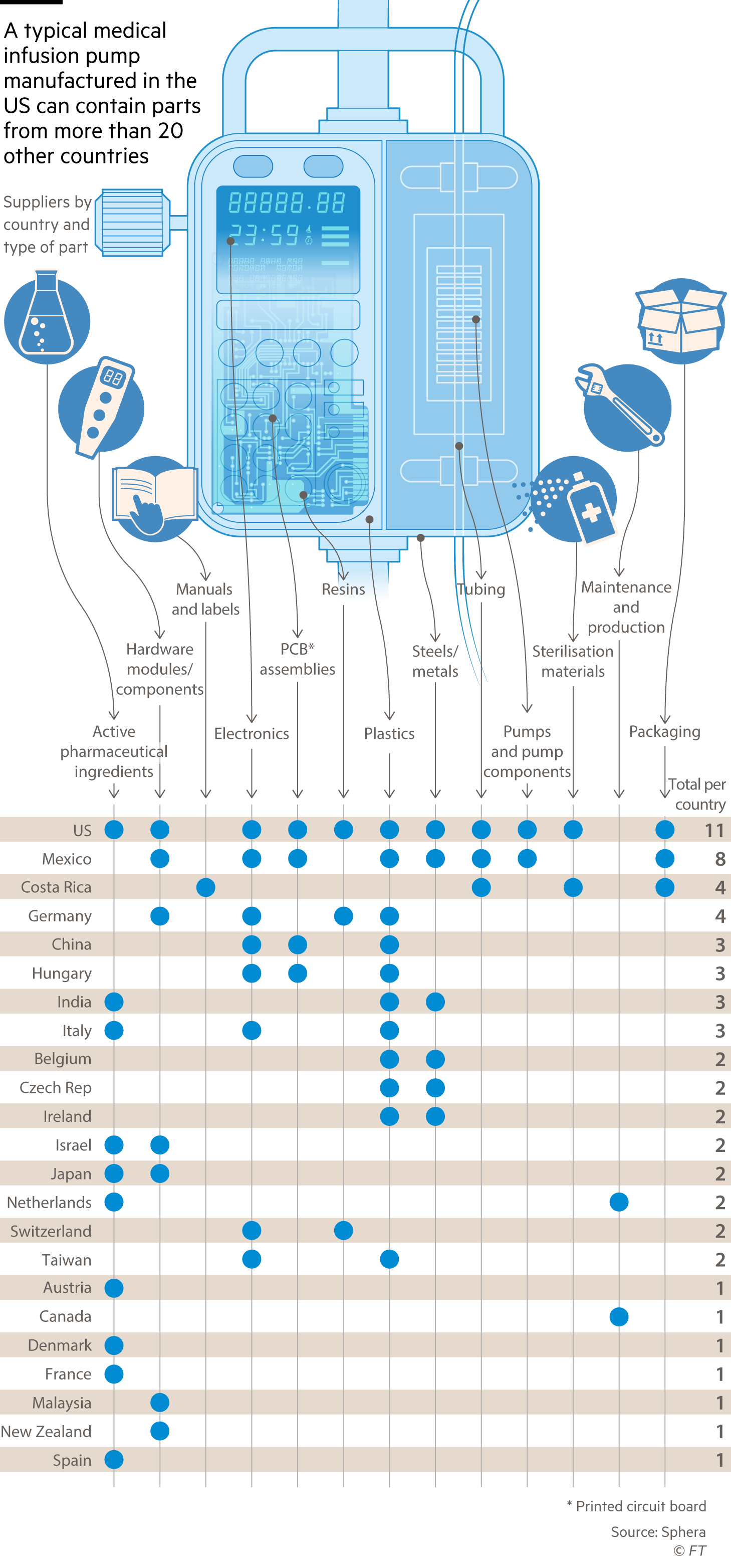

Experts said the industry’s highly integrated global supply chains, which can see a single device drawing parts from more than 20 different countries, had left the industry highly exposed to a global tariff war.

The sector’s main US lobby, representing makers of devices ranging from MRI scanners to glucose monitors, has warned of severe consequences for the health sector if the industry is not shielded from tariffs as it had been in Donald Trump’s first term as US president.

The need for regulatory approvals for individual components used in medical devices — ranging from highly complex diagnostic scanners with hundreds of parts to simple items such as surgical gloves and gowns — also constrained the ability of manufacturers to reconfigure supply chains.

Ten major US health tech lobby groups this month jointly called on the Trump administration to provide exemptions for the fast-growing industry, which is estimated to be worth more than $200bn a year in the US, according to market research groups. The lobbies represent large global manufacturers, including Medtronic, Abbott Laboratories and Johnson & Johnson.

“We are concerned that tariffs placed on medical and dental equipment threaten to disrupt the supply chain and raise costs for these critical items,” they wrote in a letter this month to US Trade Representative Jamieson Greer.

Supply chain experts said US manufacturers were most immediately at risk from the Trump administration’s 145 per cent tariffs on imports from China, which is a critical source of parts, including medical-grade polymers, metals and circuit boards.

The global industry is also facing the threat of “reciprocal” US tariffs on the EU and other components supplier countries in south-east Asia, which are on a 90-day pause pending negotiations with the Trump administration.

“US-based medical device manufacturers are, for now, the most at risk here,” said Heiko Schwarz, adviser at Sphera, the global supply chain risk management consultancy, citing US reliance on China for parts in items such as MRI scanners.

“China is the world’s second-largest exporter of MRI parts, a cornerstone technology in modern diagnostics. Tariffs on these imports could lead to substantial cost increases for US healthcare providers and patients alike,” he added.

China, India and south-east Asia are also important suppliers and refiners of medical-grade polymers, such as polypropylene and polyethylene, and high-grade metals such as titanium and stainless steel, used in implants and surgical tools.

“As the US raises tariffs on European exports and China imposes retaliatory measures, the flow of these materials is likely to slow or become more expensive,” Schwarz said, adding that tariffs could lead to “substantial cost” increases for American healthcare providers.

Legal experts said that while medical devices were not covered by the 1994 World Trade Organization agreement that exempts pharmaceuticals from tariffs, most medical devices from China were exempted from tariffs imposed in Trump’s first term since they were essential items.

Chandri Navarro, senior counsel in the international trade practice at Washington DC law firm Baker McKenzie, said tariffs on China, Mexico and Canada would impact a broad range of devices, including medical imaging and diagnostic equipment.

At the same time, she warned, the EU had included a range of medical device products from the US, including surgical gowns, stockings for varicose veins, respiratory face masks and contact lenses, on its list of products for potential retaliatory tariffs. Those countermeasures are on hold following Trump’s decision to pause “reciprocal” tariffs for 90 days.

“The newly imposed tariffs on China, Mexico, and Canada do affect medical devices. Many medical devices are manufactured in these countries and the tariffs can lead to increased costs and potential shortages,” she wrote.

Stephen Aherne, pharmaceuticals and life sciences leader at consultancy PwC, said reworking supply chains to avoid tariffs was complicated by the fact that any newly sourced parts required fresh regulatory approvals that were costly and time-consuming.

“Building alternative manufacturing capabilities takes time and requires a huge amount of effort, in terms of regulatory burdens, so a lot of companies are having to wait and see how things pan out,” he added.

A single MRI system made by a large manufacturer typically has 252 parts, sourced from 15 different countries, including China, the US and Europe, according to AdvaMed, the main US medical technology trade association.

“Each part, as well as the site where it’s made and the skills of the workers, are all registered and certified as part of the regulatory approval process. Any change to a single part or site requires an updated regulatory approval process.

“It’s this combination of a global supply chain and the regulated environment that make it particularly difficult to make rapid changes to a manufacturing process in the medical device industry,” the group said.

A full-blown tariff war between the US and China would also hurt American manufacturers looking to expand sales into China, according to Prashant Yadav, healthcare supply chains expert at the Council on Foreign Relations think-tank.

“China is a big growing market for hospital devices. The US market is pretty saturated, since all hospitals have X-ray and scanners already, but China is buying new med tech and machines because it’s building large numbers of new hospitals,” he said.

For parts coming the other way, from China to the US, Yadav said many manufacturers had buffer stocks of parts but prices would start to rise if the stand-off between the US and China was prolonged.

“A large diagnostics business might have 10,000 suppliers, of which more than 50 per cent might typically be in China and so potentially subject to import tariffs. Manufacturers will have buffer stocks, but when they get exhausted, then prices will go up.”

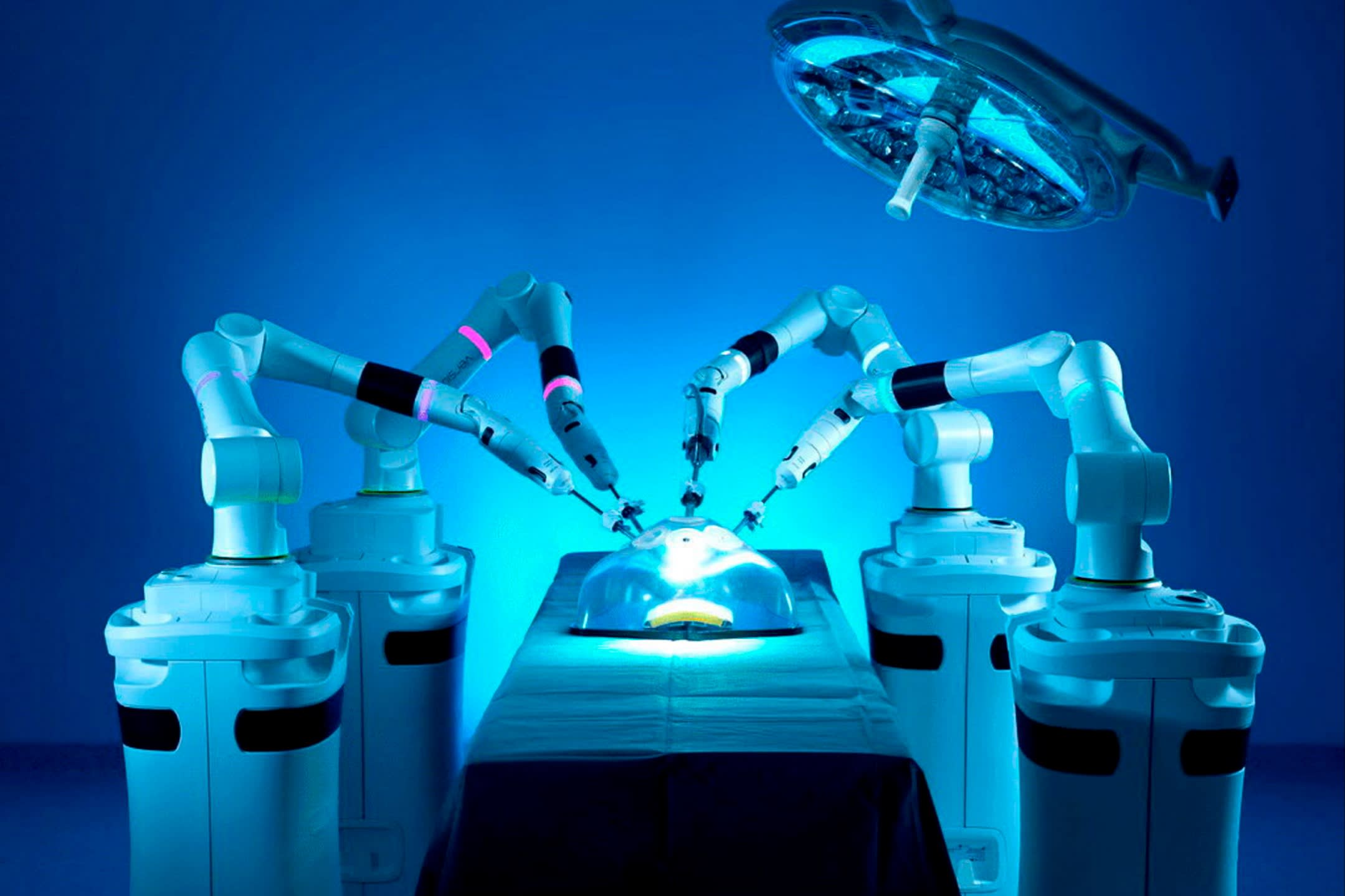

For manufacturers of high-value medical devices in Europe, such as surgical robots, even the 10 per cent global tariff imposed by the Trump administration has the potential to make it harder to be competitive in US markets.

Cambridge-based CMR Surgical, a maker of surgical robots, won regulatory approval last October from the US Food and Drug Administration for use of its Versius system that is used in procedures such as gall bladder removal.

As a result of Trump’s tariffs, the company now faces a 10 per cent tariff on exports to the US on machines that cost about £1mn, while American competitors are able to export tariff-free to the UK after the British government elected not to retaliate against the US.

CMR said in a statement that its US strategy remained unchanged and it remained committed to entering the American market, but added it was “closely monitoring trade developments and assessing any potential impact”.