Sitting in a bland conference hall in Washington on Wednesday evening, Scott Bessent presented an unabashed defence of America’s trade policies in his first face-to-face meetings with G20 counterparts.

According to those present at the dinner, on the sidelines of the IMF and World Bank spring meetings, the Treasury secretary portrayed President Donald Trump’s approach as part of a clear and masterful blueprint to rebalance the global economy — and by no means the chaotic muddle of U-turns that officials elsewhere in the world perceive.

Trump had taken “strong action” to address the imbalances of an “unfair trading system”, Bessent said at an event the same day. More than 100 countries had responded “openly and positively”, he added.

But the spring meetings of the IMF and the World Bank were marked by further reversals by Trump, which left US allies even more bewildered at what the administration is trying to achieve with its trade agenda — and more concerned at what the ongoing uncertainty is doing to their economies.

Share prices rallied after weeks of turbulence after Trump said he was ready to substantially curb tariffs of 145 per cent on China, with gains helped further by a declaration that he did not — contrary to earlier hints — plan to fire Federal Reserve chair Jay Powell.

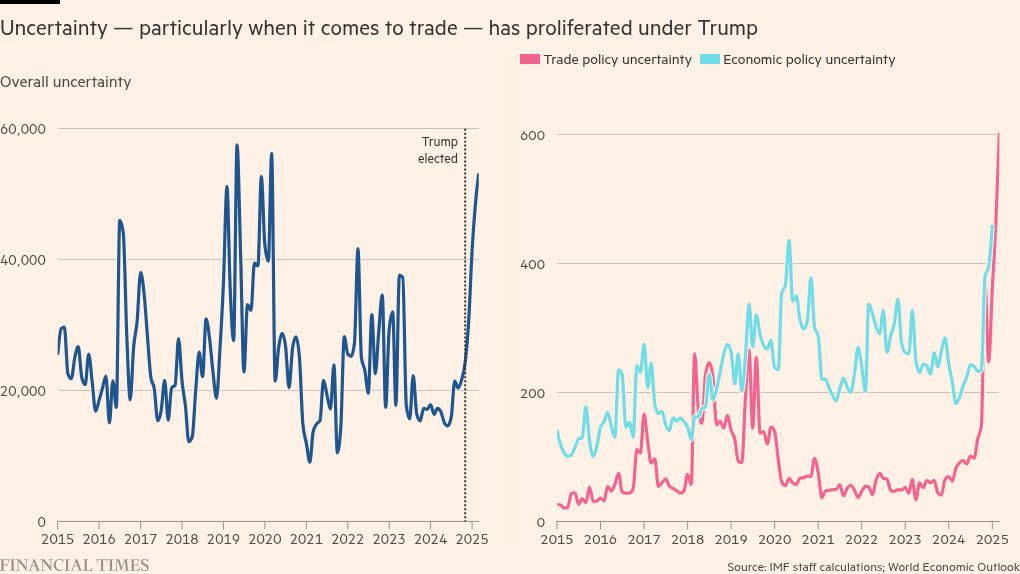

However, the IMF’s latest World Economic Outlook, released on Tuesday, warned that the instability hammering international trade would inevitably clobber global growth. “Simply put, the world economy is facing a new and major test,” said Kristalina Georgieva, the managing director at the IMF, at a press conference.

Officials and policymakers attending the meeting warned that they had no visibility as to whether the Trump administration would stick with its efforts to de-escalate its conflicts with trading partners, or resume its assault on the global marketplace.

In an acute irony, it was China’s delegates who, at the G20 dinner, presented a full-throated defence of the multilateral rules-based order that America itself originally designed, according to people briefed on the discussions.

Ministers and central bankers warned that the pervasive cloud of uncertainty emanating from the capital of the world’s most important economy was near impossible to navigate.

“What does this administration exactly want? Do they want a new trade deal? Do they want tariffs? We just don’t know,” says Eelco Heinen, the finance minister of the Netherlands.

“Right now we are going through a fog.”

After weeks of hostility, the Trump administration signalled this week it was actively seeking ways of cooling down trade conflicts with partners.

Bessent offered an olive branch to US partners at a meeting of the Institute for International Finance lobby group on Wednesday, saying “America First does not mean America alone”, and that the slogan is “a call for deeper collaboration and mutual respect among trade partners”.

This was coupled with reassuring words on the fate of the IMF and World Bank themselves. While Bessent called for them to step back from what he termed “sprawling and unfocused agendas”, he also insisted the institutions had “enduring value”.

That came as a relief to countries fretting about the prospect of outright US withdrawal from the postwar Bretton Woods institutions that have underpinned eight decades of economic multilateralism.

“The mood here is one of détente,” says one European official, noting that in meetings during the week US officials were stressing their eagerness to do deals with key US trading partners. Bessent sought to strike a conciliatory tone in meetings with his counterparts, say some officials, with the Swiss finance minister Karin Keller-Sutter praising her meeting with the Treasury secretary as “constructive”.

His deeper involvement within the administration on trade policies, as the influence has waned of Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick and trade adviser Peter Navarro, has also helped soothe officials’ and investors’ jitters.

But actually achieving tangible progress on trade relations will not be easy, officials stress. Frictions between the US and its closest partners were never far from the surface, with the official noting a “hubristic air” from the administration.

In a meeting of the G7, Bessent bridled at a question from the governor of the French central bank, François Villeroy de Galhau, about America’s yawning federal deficit, according to people briefed on the exchange.

The Treasury secretary tartly noted that he would, at the end of the week, write in his journal that a Frenchman had questioned him about his deficit, in an apparent reference to France’s own hefty borrowings. But it is the US federal deficit — at 6.4 per cent of GDP last year — which is now the larger of the two.

Officials spoke privately of conflicting messages from the administration about which US officials are actually leading trade talks, as they struggle to determine how much weight their words carry with the president.

Few doubt that Trump will remain the final arbiter of any putative deal, making the outcome of any talks particularly uncertain.

The US has repeatedly boasted of the number of governments that have been calling the White House in search of trade pacts. But if scores of countries want to do deals with the US, officials wonder how the administration will muster the bureaucratic capacity to codify the arrangements in such a short space of time — especially given the redundancies in the federal government as a result of the activities of the so-called Department of Government Efficiency.

It took 18 months, for example, for the US to negotiate a trade deal with Mexico and Canada during Trump’s first term. The president said on April 9 that his so-called reciprocal tariffs were meant to kick back in after only 90 days, ostensibly in July.

The unpredictability of US policy is making it hard for governments to do their regular budget planning, says Heinen. “What is the baseline?” he says. “This is going to hurt our economies, but to what extent is very hard to judge.”

The lack of visibility was underscored in the IMF’s twice yearly survey published this week. The “extremely high levels of policy ambiguity” had made it difficult to put forward a central outlook, the IMF said, meaning it took the unusual step of presenting “a range of global growth projections”.

One of these posited that Trump might extend the pause to so-called reciprocal tariffs indefinitely. Even if this happens, however, it would not “materially change” the baseline outlook because of the magnitude of the trade barriers now being erected between the US and China, the world’s two largest economies. “The membership is anxious,” said Georgieva, the managing director at the IMF, at a press conference.

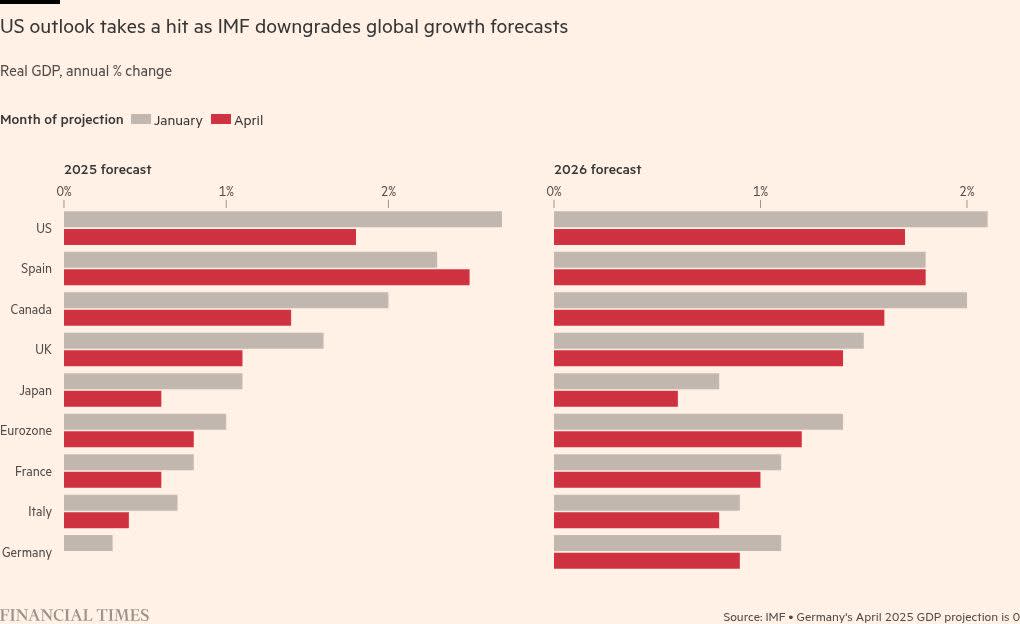

As recently as January the fund had been predicting 3.3 per cent output growth this year globally, she said, and was worried that this was not strong enough. Now the fund is expecting growth of just 2.8 per cent.

During the week the German government, for example, cut its 2025 growth forecast for its trade-reliant economy to zero from 0.3 per cent previously. On Friday consultancy Capital Economics said it had cut its Eurozone GDP forecast because of the tariffs, predicting near-zero growth in the second and third quarters.

“The longer we wait for an agreement [on trade], the longer we let the uncertainty in both of our economies linger,” said Jörg Kukies, the German finance minister, at an event on Wednesday. “I just don’t see that as a positive.”

It was the US itself, however, that suffered the biggest growth downgrade among the G7 economies.

Pointing to acute self-inflicted damage from Trump’s policies, the fund cut its 2025 forecast for US growth by nearly a percentage point to 1.8 per cent and put the odds of a recession at almost two in five.

Some analysts argued even those figures were still way too rosy. The downgrade was much smaller than in the summer of 2022, for example, when the IMF cut its growth forecast for the US by 1.4 percentage points following the outbreak of war in Ukraine. Elsewhere in Washington, the Peterson Institute think-tank has cut its forecast for US expansion this year to just 0.1 per cent.

“There are going to be Covid-like interruptions in the supply of things,” says Adam Posen, president of the institute. “It’s not going to be as dramatic as 2020, but it can be abrupt and sizeable.”

He said the auto and housing sectors face shortages of key supplies from China, alongside price hikes that are making certain components unaffordable.

Analysis from Sea-Intelligence has shown a rise in the number of cancelled transpacific sailings. The German shipping giant Hapag-Lloyd said this week it had seen 30 per cent of its sailings to the US from China cancelled.

“China at present imports very few things from the US that it can’t get from others, including money,” says Posen. “The US imports all kinds of things that we can’t get from anyone other than China at speed, or at affordable prices.”

Retailers are worried that shelves will be left empty because of the height of the barriers being imposed on Beijing. China made 75 per cent of the dolls, tricycles, scooters and other wheeled toys delivered to US consumers from abroad last year, for example.

The world’s largest consumer packaged goods groups warned of retrenchment among shoppers. Procter & Gamble, PepsiCo, Colgate-Palmolive and Kimberly-Clark all cut sales or profit forecasts, with some pointing to higher costs from tariffs and deteriorating consumer confidence.

Andre Schulten, chief financial officer of P&G — the US-based company with brands including Olay skin creams and Crest toothpaste — said executives began to see the market slow down in the US and Europe. Consumers were concerned by the declining stock market, politics and the economic outlook, he said.

“You name it, all of those volatile elements play into the consumer behaviour, including tariffs, and if you put it all together, it’s not illogical to see the consumer adopt a wait-and-see attitude,” Schulten told reporters.

Both the fund and US officials have flagged that the world’s largest economy was, at the turn of this year, in a strong place, and the hard economic data has yet to show significant signs of strain.

But warnings of a slowdown are growing louder. Torsten Sløk, chief economist of hedge fund Apollo, put the odds of what he called a “voluntary trade reset recession” at 90 per cent. “Expect ships to sit offshore, orders to be cancelled, and well-run generational retailers to file for bankruptcy,” he wrote on April 19.

And while policymakers at the Bank of England, European Central Bank and elsewhere are ready to cut rates to alleviate the drag from the trade war, US consumers and businesses may need to wait for easier monetary policy.

Federal Reserve officials want borrowing costs to remain where they are until they are convinced that the rising trade barriers will not trigger a fresh bout of persistent inflation.

That is despite the central bank’s latest Beige Book, a compilation of US business and household sentiment, warning on Wednesday of “pervasive” uncertainty because of international trade.

The White House’s apparent appetite for de-escalating trade tensions, especially with China, was seen by some delegates at the spring meetings as evidence that the US feels backed into a corner.

One spoke of an air of economic “doom and gloom” hanging over Washington, with rising anxiety about the self-inflicted wounds stemming from the trade war. “This is the real world hitting them in the face pretty hard,” says a European official.

China appears to be refusing to march to America’s pace. Trump this week claimed his administration was talking to China on trade, but Beijing denied the existence of negotiations and demanded the US revoke unilateral tariffs if it wanted talks.

Stephen Miran, the chair of Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers, hit back at any suggestion that China had the upper hand.

“We can make stuff at home. We can buy from other countries that we make trade deals with that treat us better in trade than China treats us,” Miran said to a packed room at the Dupont Circle Hotel on Thursday afternoon.

But he too suggested there would be “some means of lowering the temperature” with Beijing “in the coming days, the coming weeks”, hailing Trump as “one of the world’s greatest negotiators”. China on Friday granted some tariff exemptions on US imports, in a move that relieved US businesses operating there.

Some economists believe the US will be forced into a climbdown over concerns about a sudden stop of key imports from China. Holger Schmieding, chief economist at Berenberg bank, predicts Trump will negotiate away roughly half of the extra tariffs within months.

If not, he says, the US will be the “major victim” of trade-war policy, hurting its own growth prospects even more than those of regions such as Europe.

Even if Trump has now embarked on a path to at least partial détente, resolving the situation will not be easy. “Trade talks will probably be rough, with many US threats to leave the table,” says Schmieding. “In the meantime, uncertainty will reign supreme.”

Speaking at a breakfast on Friday, Bessent told counterparts privately that he believed the peak of instability had now passed.

But many are not convinced. One former central banker, asked if officials would be leaving Washington more optimistic than when they arrived, says: “Absolutely not.”

“It will take actions, not just words,” he says. “Credibility has been eroded.”

Additional reporting from Stephanie Stacey in Washington and Gregory Meyer in New York

Data visualisation by Ray Douglas